Film Information

Set in Antananarivo, Madagascar, Chez les Zebus Francophones (Where Zenus Speak French) cautions about the continuing plight of dispossession in postcolonial Africa. The indigenous Malagasy struggle to prevent the encroaching industrialisation which drives them off their farms to the benefit of foreign multinational corporations and agribusiness investors.

Directed by Nantenaina Lova, the documentary neatly merges surreal storytelling with rough reality, creating room to humanise the endearing Malagasy peasant farmers while also displaying their resilience and sturdiness against the prevailing threat to their way of life.

CITY OF SACRED HILLS

Antananarivo is the largest city in Madagascar. Folklore has it that historically, the city was swampland populated by crocodiles. Soon the swamps gave way to rice paddies, encouraging an agricultural way of life where communities grow food for subsistence and for sale.

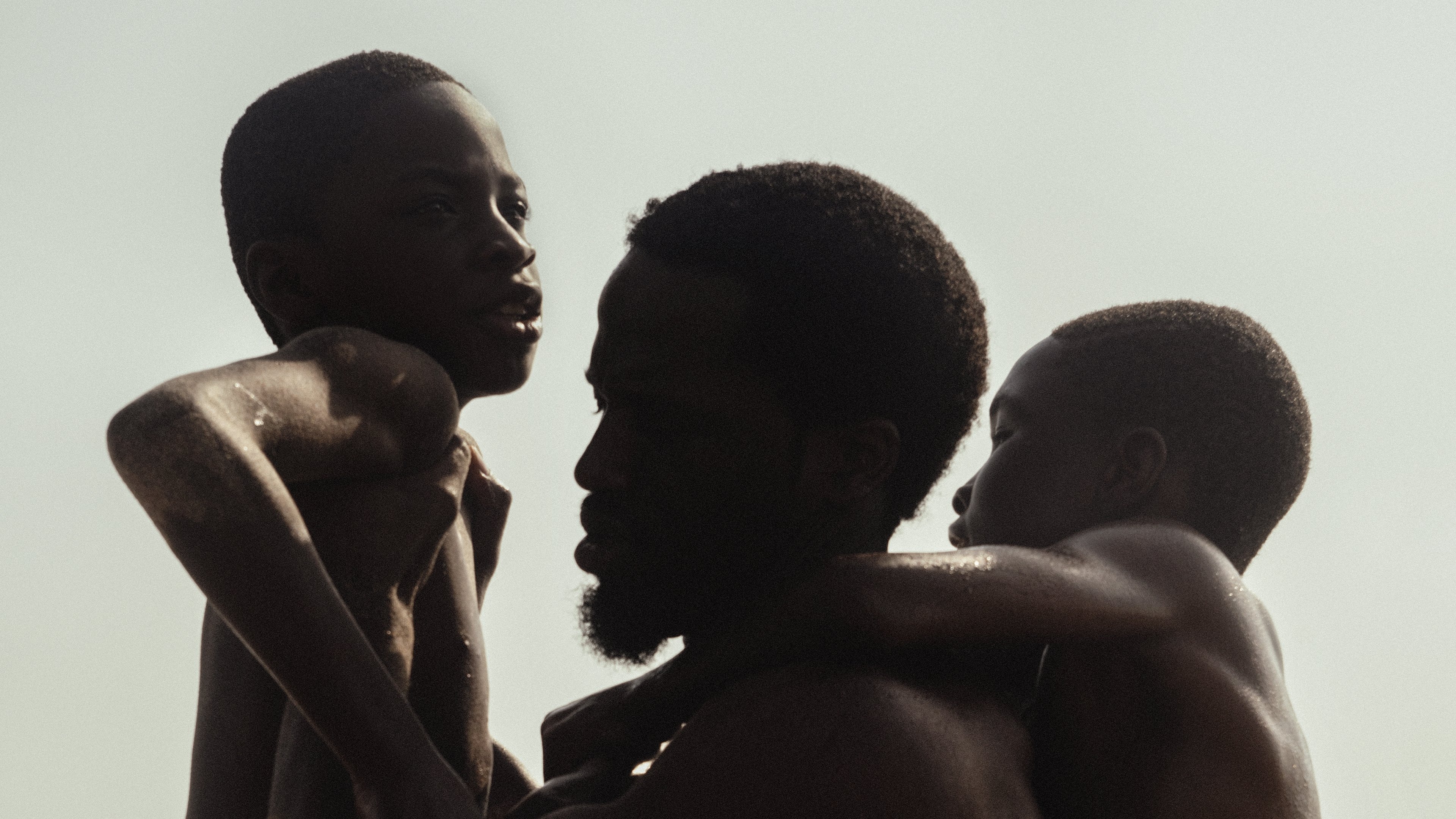

Rural activities are filled with joy and communion. Children dance on logs. Pots rest on wooden fire. Storytellers make wooden puppets and narrate the history of the city. The children adopt these traditional makeshift toys, dolls and wooden cars, forming their own stories. There is also much labour with the tilling of soil and directing of the titular zebus to plough the fields.

There is a widely repeated saying, raha noana nu fanahy, mivezivezy ny vatana (if the soul is hungry, the body is lost). Thus we are introduced to people who are both physically and spiritually self-reliant.

To designate between farmlands, families plant eucalyptus trees. Farmers use indigenous knowledge for subsistence crop growth, avoiding chemical fertilisers Organic for subsistence. Some use these chemicals in their rice paddies for increased yield, since they also grow food for income.

THE BOMB OF CAPITAL

Attached to this message is a visual medley of Sitabaomba (Bomb Site), as it is called, a damaged and undeveloped area where locals live informally without land use rights. The remnants of historical conflict, colonialism and conquest are visible in its ruin. The latest in this cycle of crises has been caused by capitalism.

Before, this place was known as a banana grove, but now the only bananas grow far off-camera. There are still means of survival. People farm rice, vegetables, fish and ducks. But the state has implemented a system of land titles which conveniently are only awarded to multinationals and agribusinesses, who evict families who have cultivated their land for generations. The film's narrator points out that one can only cut down a tree with the collusion of the wooden handle. Here, the state is shown to facilitate the process of dispossession of its people's livelihood.

Swamps are the identity of Antananarivo, visible from drone footage above, but they are being filled in. Plots are being sold without the tenants' input. Bulldozers have no concern for the farmers' crops.

The government has offered no solution to the farmers. Rural dwellers do not have diplomas to do office jobs in the city. If they move deeper into the outskirts, they face theft from bandits, which is already a pressing issue. Crucially, the farmers feel connected to their land. They do not want to move, especially not so they can be replaced by industrialists.

Yet, industry argues that indigenous ways have to change due to changing times. The country's president has prioritised building a road toward the airport for international visitors and dignitaries, further displacing farmers on the road's route, while also promising away mining rights to finance the road's construction. The president claimed that the hallmark of their presidency would be eradicating poverty by moving from subsistence farming to industry, but instead, it was the displacement of peasant farmers to give land to their army generals.

The subsistence farmers were only used for photo operations and offered meagre compensation for their dispossession. The state's soldiers assist in bulldozing efforts and the government either ignores court summons to address the plight of the peasant farmers or manipulates trial hearings.

Worse of all, the closing of rice paddies is creating rice shortages, forcing a country where 80% of its economy is agriculture, to import rice. On many levels, the documentary shows the gradual destruction of indigenous life, metaphorically ticking the bomb to complete dispossession.

THE FUTURE IS BEHIND US

The Malagasy try to hold on to their traditional ways. They have formed a farmers association to review development projects and lobby the government. They create dramatic reenactments with their wooden puppets and even use modern film to communicate their message, using film actors who have also experienced the same land confiscations.

One of the main characters followed by the film is Jean Loius, nicknamed Ly, who is a family-man that tries every effort to save their farm, even moving it to less desirable land to avoid the landgrabs. When his crops are razed down, he plants anew. He contests for positions in local authorities, who are complicit with the sale of land.

The farmers association also intensifies its efforts through confrontations and assemblies, aimed at creating power through numbers and taking back control of their land.

A new president is elected in Madagascar, who also launches their own ambitious development project, which will continue to dispossess the farmers, despite promising against this on the campaign trail.

In this way, a local adage which states that the future is behind us becomes true. The past is everything that we see in front of us. We are aware of everything we have experienced. The future creeps up behind us unaware.

Yet, the documentary's narrator, who repeatedly brought in the perspectives of the Malagasy people on the history of their exploitation, reminds us that the locals are still firmly planted in their roots. 'We weave our lives into our stories'. Farmers bring life to land. Industrialists destroy. For the peasant communities in Madagascar, they need to, as best as they can, hold on.